Blog Archives

The San Pedro River, Doug Tompkins, and the rise of Ecologically Aesthetic Action Part I

Photo Credit: David Mendosa

If future generations are to remember us more with gratitude than sorrow, we must achieve more than just the miracles of technology. We must also leave them a glimpse of the world as it was created, not just as it looked when we got through with it. ~ Lyndon B. Johnson

There is a river in Arizona that is alive in my mind. I’ve never walked its banks and listened to its softly gurgling sounds, or felt a shift in the air from the presence of hundreds of species of birds in the trees overhead, or even glimpsed a section of the strange green band making its way 140 miles north from Sonora, Mexico, across the U.S. border and through the Madrean Archipelago, or Sky Islands, in a desert sea to the confluence with the Gila River – but I’d like to. It sounds like a place out of a fairy tale or a dream and if I couldn’t prove it existed, I wouldn’t believe it was real.

The San Pedro River is a corridor of life slicing its way through the Sonoran Desert. It plays host to the largest diversity of mammals and half of the bird species (400 species) in the continental United States. The desert is not often a place we imagine teaming with life, but where there is water the desert flourishes. The San Pedro River is significant on the scale of the Colorado River, not because it provides water to millions of people, but because it is the last free-flowing river in the southwest upon which the single largest array of biological diversity in the U.S. depends.

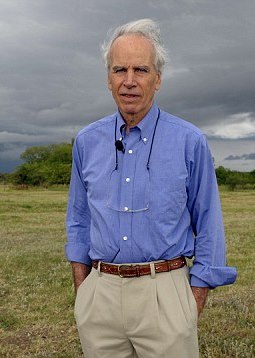

Doug Tompkins, Getty Image

The mere existence of this un-dammed river calls like an echo from the footsteps of the late conservationist Doug Tompkins. It is a sad state of affairs that we start listening to someone after they have died, but it is better to listen late than to never listen at all. His legacy is like a beacon offering guidance for those navigating the foggy sea of environmental protection and restoration. As I read about the San Pedro River and my alarm began to grow, the words and actions and leadership of Doug Tompkins suddenly came into focus.

Though I did not know Tompkins personally, I was moved by his genuine passion and concern for the land and natural processes when I watched and listened to him in the film 180˚ South. I believed his sincerity then, but was moved to act upon his death after pouring over all the obituaries that followed his fatal kayaking accident and learned more about his life’s work. As I struggled to imagine what Doug would do to fight for this river, I came to the conclusion that no matter how he chose to do it, he would fight the voracious tapping of groundwater as persistently as he did dams in South America.

Like most rivers in the desert, the San Pedro is fed by groundwater that rises to the surface through a spring into what is known as a ciénega, or marsh. Ninety-nine percent of all ciénegas in the southwest have been drained or destroyed. The Nature Conservancy owns several preserves on the San Pedro River including Ranchos Los Fresnos located near the river’s source, which is the largest ciénega remaining in the San Pedro River watershed. But that doesn’t mean the river is protected.

In Arizona, water law is counter-intuitive and scientifically absurd. Let me explain it like this: Surface water and groundwater are seen as separate entities, so owning surface water is like having a soda that someone else has a straw to. The surface water can quite literally be sucked away by other users via groundwater pumping. And that is what’s happening to the San Pedro River. The more the groundwater gets pumped, the more the river shrinks, and as it recedes, the vegetation recedes with it. If this once perennial river recedes enough and the cottonwood trees growing alongside it die, the entire ecosystem will collapse.

We do have federal laws that by all rights should protect the San Pedro River, but strangely, state representatives have the power to undermine those federal laws with the strike of a pen. They do this through riders inserted into appropriations bills passed in Congress. How this is legal or even allowable is beyond the scope of reason.

Richard George “Rick” Renzy, Photo Credit: Wikipedia

The San Pedro River Riparian Area was designated America’s first Riparian National Conservation Area in 1988. Because of that, the BLM owns much of the surface water as well as the land around it. If that was not enough to protect it, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) would protect the river by default in order to protect the water-dependent endangered species that live there. But thanks to former Representative Renzy of Arizona, and Senator John McCain, none of that protection means anything for the San Pedro. In an appropriations bill, Rick Renzy introduced what is known as the “Renzy Rider” that exempted the Department of Defense, i.e., Fort Huachuca and the surrounding community of Sierra Vista, from the ESA requirements and Senator McCain supported it.

Federal environmental law, or any law for that matter, cannot work if legislators in Congress can slide subversive riders into foxholes within appropriations bills. By doing this Congress is violating the very laws it is meant to uphold. Furthermore, it is legally lazy. Riders abdicate Congress members of their duty to work within limits.

We don’t always get what we want, and when we reach limits, we must work creatively within them rather than pretend they are not there. This is called innovation. Innovation is the by-product of limitations. We will never progress if we do not abide or accept the confines of reality; to do otherwise is willful lunacy. Our laws, which help guide our actions, are meaningless if they are not upheld and enforced by those in the highest offices of government.

Furthermore, if the hope of getting something set in law requires that a rider be attached to and buried in an appropriations bill, and if it undermines or makes a mockery of standing law in the process, then it’s probably a bad idea and is surely questionable, if not unethical, and calls for a legal remedy.

The only way environmental protection or justice will prevail is if such actions by members of Congress are not scrutinized and condemned. Any proposal by any member in Congress should have to pass a legal litmus in that if what they are proposing violates current law, there should be a process by which it is weighed and measured and possibly dismissed or thrown out. The Renzy Rider is certainly a case worth challenging.

But what is at stake here is more than what is legally allowed or disallowed. What is really at stake is ecological integrity, or beauty – not beauty in the cultural sense, but beauty in the philosophical sense – beauty meaning value and the ethics involved in maintaining or destroying it. Taking a classical baseline to build from, beauty has historically been a value argued to be equivalent to truth, goodness, and justice and is determined by the arrangement of the parts that make up the whole.

Philosophically speaking, a beautiful object is measurable, proportionate, and harmonious and is something that brings pleasure to the observer. Something that is disproportionate, distorted, or out of balance is either inherently not beautiful, or once was beautiful and has been debased or destroyed. Based on the scientific knowledge we have amassed on the environment, we know that the environment is an intricate web of life that is made up of many parts and layers contingent upon each other for the health, well-being, and structure – or beauty – of the whole.

The parts of the environment can be objectively or subjectively beautiful, some parts can even be considered visually ugly but still be beautiful by aesthetic standards. But those parts that make up the the whole come together to create and sustain life and life is nothing if it is not a miraculous display of art. Not just man-made art, but un-made, natural, and discoverable art that is intricate and delicate; interactive and dangerous. It is a shifting, moving, and dynamic force that cannot be contained or showcased in a building without being mirrored through the hands of human beings. Artwork reflects the mirror of the mind touched by life. The source from which art is born and discovered demands respect, care, and protection as surely as the artwork itself.

But it is so much more than merely something to be viewed; it is the indescribable natural processes and phenomenon that we are a part of and belong to, and it is through the context of pleasure and pain that we truly grasp the magnitude of its grandeur. It is the myriad ways in which we get to experience the elements coming together to form what can only be described as the sublime.

The sublime is the sensory awakening and awe-inspired response to seeing, feeling, smelling, and hearing raw, natural beauty: watching the light shift and move across the Grand Canyon, hearing the crashing waves of the ocean responding to El Nino effects, the smell of rain before a thunderstorm rolls in, the bitter-sweet experience of summitting a strenuous mountain, the thrill and fear of watching a predator chase prey, the sense of wonder at a river seemingly defying logic by running north through the desert, and the dance between human mortality and natural power at play in the struggle for life.

Summer monsoons in the southwest

While these earthly processes and phenomenon have been happening for eons, and humanity has been observing them for thousands of years, we are fleeting; our time here is short. But our ideas are not. Ideas are like seeds that take root and grow and produce fruit that outlast us. One of the most significant ideas to take root and flourish was the philosophy that organization could dominate and replace nature.

According to Vision and Politics, the philosophy of organization as articulated by Saint-Simon “connoted far more than a condition of social harmony and political stability. It promised the creation of a new structure of power. As a system of power, organization would enable men to exploit nature in a systematic fashion and thereby bring society to an unprecedented plateau of material prosperity.”

Nature has historically been the great leveler. It was impartial in its release or withdrawal on humanity. Our response, unfortunately, has been to tame or destroy it rather than learn about it and work within it. While toiling for security, stability, and bounty we have forgotten to look around at our handiwork and assess if it still makes sense from a wise and sustainable standard. By turning individuals into functions of organizations, we have become astoundingly efficient at producing material wealth – perhaps too efficient. And that is the underlying cause of our dilemma and the foundational idea that drives and controls much of our collective behavior today.

We have operated from a paradigm that sees the fulfillment of desire and economic prosperity as paramount rather than one of sustainable abundance and moral refinement, both of which reflect the wisdom of restraint. Despite the magnitude of beauty and value the world holds we have been and still are reducing and destroying it, and today we are doing it with our eyes wide open. We are not ignorant to the effects of our actions. In the past we couldn’t see what we were doing because we didn’t know what we were doing. That is not true today. We know, we see, and we have no excuse to continue on this path.

But it doesn’t have to be this way, we can choose another path, one that accepts reality and natural limits and tries to walk in harmony with it. By doing this we not only act ethically and responsibly, we find beauty, meaning, and purification by being a part of it rather than trying to eradicate or separate ourselves from it.

According to Rousseau, only in nature does one find equality, freedom, and independence. Those are words that we value, but find frightening when experienced in nature. The reason is that you have no control over how nature deals the cards. In it one finds the tranquil but also the dangerous that can heal, challenge, and destroy. It is this razor sharp edge between life and death, of comfort or struggle, that makes nature terrifyingly beautiful. Through it we become aware of our mortality and the finite time we have here. Some of us shun it in favor of comfort and ease, others face it in order to do something worthwhile or to feel alive.

It is this choice that defines and shapes us and it is ultimately the reality of our finitism, of resource finitism, of species finitism, that should compel us to act ethically with the finite time we have here. We only get one shot to do something that lasts beyond our lifetime, and then only time and consequence will tell if it was meaningful and good or short-sighted and foolish.

When we face the challenges and limits imposed by nature we get distilled down to our most basic essence and become our truest selves. Nature reflects back to us who we are, and through it, we become less like functioning parts and more like individuals; more human, more awake, and more alive. Our lives and actions become refined through the challenges of nature and history will reveal either the subtle beauty or destruction of our choices.

Continued in Part II

Sources:

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Environmental Aesthetics

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: The Concept of the Aesthetic

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Beauty

Tuscon.com, Arizona Daily Press: Massive Benson development wins approval,

Tuscon.com, Arizona Daily Press: Development would make Benson 8 times bigger

Audubon Magazine: Housing development could threaten Arizona’s San Pedro River

John McCain and the Renzy Rider, http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/media-archive/SanPedroMcCain6-26-08.pdf

Contemporary Aesthetics and the Neglect of Natural Beauty, R.W. Hepburn: http://hettingern.people.cofc.edu/Env_Aes_2012/r_w_hepburn_contemporary_aesthetics.pdf

Wolin, Sheldon S. (2006). Politics and Vision. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

The Story of a Flower: From community member, to endangered species, to public enemy – Is it time for a new narrative?

Desert Globe Mallow, photo courtesy of chicbee04 @ http://www.flickr.com

Every spring, as the days begin to grow longer and the weather consistently warms, my eyes start scanning the horizon for very specific plants, vegetative cues that mark the passage of time from one season to another. One of those plants is the Globe Mallow. Their presence marks the transition from spring to summer. Bright orange bushes burst into flame along highways, freeways, and across the desert floor. They are flowers that you must see up close to truly appreciate. The small petals form little bowls, globes, or women’s skirts, that when filled with light, glow softly. Delicate like tissue paper, they are enchantingly beautiful. When they bloom I make a yearly pilgrimage with my boys to explore the changed landscape for the short period that they are blossoming. Though I don’t know much about the niche the Globe Mallow fills, or about the other species connected to or relying on them, they provide aesthetic pleasure, joy, and wellbeing to my life. I enjoy them. They are a part of the community in which I belong. They are a part of my story. If they suddenly disappeared, I would miss them, wonder about them, and seek to discover what had happened to them. They do not provide food or shelter and I’m not sure of their economic value, but they hold value to me. They ground me in time and place.

If the Globe Mallow was facing extinction I would feel an urgency to protect it. I would feel its loss before it was gone and would work to avoid that reality. If, however, a barrier was put around the flower that kept me away in order for the government to protect it, I would feel helpless. It would no longer be a part of the same world as the one I am in; it would be separate, sanctioned off. I would hope that the government would be able to ensure its existence, but I would no longer feel a part of its presence or protection. I could only hope. My interaction with it would be similar to looking at it through protective glass.

Though not all species provide this sort of personal connection to me, all it would take to change that would be intimate knowledge. Kind of the same way a person changes from a stranger to a friend. For example, I know that if I rub creosote leaves between my fingers, it smells like rain. I know that sage provides a pungent fragrance that seems to permeate and rise up out of the earth. I know that right before autumn and a chill can be felt in the air, tarantulas come out. Knowing ones community happens subconsciously and almost intuitively, but turning that knowledge into love usually takes an act of conscious and willful acknowledgment and recognition. Often this is brought about through someone else’s actions, like the demolition of a hill. Sometimes is comes through absence, like when we move away. But without knowing a place, we cannot love it, and if we don’t love it, we won’t protect it, and if we don’t protect it, it will disappear.

“Life is a miracle,” said Wendell Berry, “One kind of evil certainly is the willingness to destroy what we cannot make – life, for instance.” Life, including ours, plants, and animals, but also, the elements that sustain life such as water, soil, nutrients, and sunlight; in other words, the cycle of life and all of its interconnected parts and dependencies, is a miracle. Utter extinction, pollution to the point of poisoning life, annihilation of life giving properties, is unacceptable to us and virtually unfathomable, but it is happening. These changes are on a large and slow enough scale that if we choose not to see it, we won’t. But when we narrow the scope, bring it down to our own backyard, we can’t help but see it and be impacted by it. We need to take our backyard and apply it on a global scale to take what matters to us and expand it to the world; amplify it across borders and landscape to people and communities not so different from ours, and interestingly, not so far removed from ours either.

Robert McKee said, “On one side is the world as we believe it to be, on the other is reality as it actually is. In between is the nexus of story.” This is the story of a flower, a close relative to the Globe Mallow, and some of the people living and working in proximity to it. Living in remote and small sections of the Mojave Desert in Utah and Arizona is the Gierisch Mallow, a rare and largely unknown flower found nowhere else on earth. It grows in a crusted, gypsum soil suitable only for unique species that holds nitrogen, moisture, and stays erosion. The flower is believed to be pollinated by the same bees that pollinate the Desert Globe Mallow, a flower found in much larger numbers throughout the southwest. The bees nest in the ground, within range of the flowers. A combination of evolutionary adaptations have produced a habitat suitable for the flowers to grow and survive in. Without the ability to travel the way we do, we might never have known of their existence.

Last year the Gierisch Mallow was listed as an Endangered Species. Prior to the listing I attended a meeting held by the BLM for stakeholders who would be impacted by the designation. I attended to hear what the local ranchers and miners had to say. Knowing the general disdain for anything environmental in Utah and that the local ranchers and miners held strong beliefs about mankind’s role in it, I wanted to hear how they would articulate it and work within the confines of a government setting. As I watched the two groups, two distinct narratives formed in my mind: one was scientific, the other religious. The ranchers did not want the plant listed, and though the BLM employees were following a process, I presumed they supported the designation. Though the process is meant to be objective, deeply held narratives were driving it. One narrative is the desire to protect life through public policy based on scientific analysis and evidence, the other is the desire to maintain a way of life based on a belief that God gave us dominion over the earth. Though none of this was spoken, it was there under the surface.

While the life of the flower was never directly discussed, and was actually never in question, how to go about protecting it was. The local miners and ranchers did most of the talking. They not only felt betrayed, they were worried about what the listing would mean for their way of life and bottom line. Realizing that the ranchers had been collecting seeds from the Gierisch Mallow and had been providing them to the BLM in an effort to work proactively, their anger and disappointment at an outside group requesting the designation and undermining their efforts was understandable. Though they never spoke of the fragility, beauty, or right of the flower to exist, it was clear that everyone recognized this by their preemptive actions in trying to protect the flower before the listing. At the heart of this meeting was a deep suspicion, based on collective experience, that one, the locals would carelessly trample the flower into extinction, and two, the government would come in and determine that the flower held more weight than the people living there. The locals were certain they could protect the flower that lived among them and pleaded their case. What they got was a bureaucratic answer that they could make comments during the scoping process and possibly sway the decision and course of action. Once the plant was submitted as a candidate, the land management agency was required by law to follow regulations to determine its status.

The Endangered Species Act maintains that our natural heritage, plants and animals, have aesthetic, ecological, educational, recreational, and scientific value for this country and the people. Those are the values that get analyzed and discussed through the process of a listing. While the language appears to be inclusive, the Act ignores the relationship between people and the species and subsequently, the land. This exclusion of the relationship and personal narratives behind it makes the process sterile and impersonal. It isolates the species from the people, the place, and the ecological community they all belong to and makes it “other.” To compartmentalize the humans, from the species, from the land, is to keep all of the parts of a specific environment separate, and thus work against the end goal of maintaining the ecological health and integrity of the whole. Rather than using the local population to maintain and protect the plant, they are excluded. This segregation reinforces deeply held narratives that people hold to non-human life and to the earth.

The narratives that shape people’s perceptions and attitudes are as varied as the people, but there are extreme ends in the environmental debate. Though there are many shades of grey in beliefs toward the earth, it is the stereotypical types on both ends that get all the attention. The extreme narrative of the bible-based religious demographic is that God gave humans dominance over the earth, that we were made in God’s image and that ultimately, humans take priority over all living and non-living life on earth. The extreme environmental narrative is that all living and non-living, non-human life has intrinsic worth and is equal in value to humans and therefore, should be given equal standing when it comes to decisions affecting it. When a species gets protected and it inhibits human behavior, industry, and livelihood, the two clash and depending on how the decision unfolds, ill feelings and antagonism result. This end result is bad for both sides because instead of finding sensible solutions in the future, the people will simply oppose each other over any policy decision. If these policies keep ignoring the narratives of the local populations affected by them, the deeply held beliefs will be reinforced and progress will face stiffer and stiffer polarization and legal battles.

But when our decisions affect life, even if that life doesn’t seem significant, we need compassionate narratives that work creatively and ethically to protect the web of life, both human and non-human. It is easier to take an issue that obviously needs addressing, such as clean water, and have consensus, but protecting an unknown species can leave much open for debate. This is where policy fails us and story can help. As Robert McKee stated, “Values, the positive and negative charges of life, are at the soul of the art of storytelling. They can shape a perception of what’s worth living for, what’s worth dying for, what’s foolish to pursue, and the meaning of justice and truth.” It is not the worth of the flower or its existence that is at stake; it is the worth of the ones valuing that is at stake. At the core of environmental conflict is the messy relationship between people. Relating and finding common ground is easier done through narrative than policy because narrative allows empathy to surface. The gift of learning someone’s story is that it provides the opportunity to live lives beyond our own, to desire and struggle in a myriad of worlds and times, at all the various depths of our being (McKee, pg. 142). When we do that, we empathize and through empathy, link ourselves to another human being, testing and stretching our own humanity (McKee, 142).

As I sat as an observer at the BLM office listening to the local field office employees and the local people, I wondered about the missing group, the one that had proposed the listing. While I was certain they had good intentions and their mission probably states a desire to protect all species, I couldn’t help wondering: Have they been out here? Have they even seen the flower? How different would it be if they had talked to the people impacted by the designation and had learned their story? I wanted to know if the flower was in danger of extinction due to human impact, or if it was just a rare species with a small population. As I let my imagination go, I imagined the people who live and work out in the Mojave Desert and what their life was like. I am certain they not only have stories, but history there, that is personal and intimate in a way that we can only relate to by comparing it to our own place. I was certain, that like me and the Desert Globe Mallow, the men in the room also know the seasonal cues, love the landscape, and are aware of the nuances of life found there. The plants and species are not just names in a database; In other words, the people living in these remote places are familiar with the species and landscape in a way that only a local could be. While they might shape their narrative along familial and traditional stories, and may even accept and include the growing scientific evidence as guidelines for their behavior, it is their personal story being threatened.

The story of the Gierisch Mallow is not just of the flower and its beauty; it is about the beauty of the flower in context. The story includes the land, the inter-relationships of other species, and of the people who live and work in proximity to it. Depending on the narrative you subscribe to, the listing of the Gierisch Mallow is either beautiful or tragic, or perhaps it is both. In the reality of environmentalism, we are burdened by our heritage, but the story can be changed and rewritten to produce renewal and cleansing through humble, respectful, and well-told stories.

The Gierisch Mallow is just one species of many that have been entered into the narrative of species protection and extinction and the people involved. How will it unfold? Will the locals harbor good or ill will toward it? Will they resent those designating it, despite their good intentions? Will their story be a happy ending or a tragedy? It will be determined through their narrative filter. The story is ultimately one of life and how we value it, both human and non-human.

A flower offers a simple yet powerful metaphor for life. From time immemorial, flowers have been recognized for their beauty in scent, color, and form. In the short timeframe of their life cycle we see the duality of beauty and tragedy, life and death. They remind us of the passage of time. The word beauty originates from the Greek word hora, meaning ‘hour.’ It is associated with “being in one’s hour.” When a flower is in bloom, it is in its hour. The flower’s beauty, delicacy, and moment in bloom elicit an emotional stirring in us because the pinnacle of its beauty is fleeting. Because of the fleeting nature of life and the passing beauty in it, we often try to capture and prolong the essence of it through artistic reproduction, but art only makes static what is transitory.

Like a stunning sunset whose beauty lies in its temporal nature, we relish it because it won’t last, but even if we could stop time, we would not want to live in perpetual dusk. It is the moment between birth and death, the passage of time that captures our imagination. Nothing we can do will prolong the scent of a lilac or the form of a rose indefinitely, but we know the cycle of the plants, we know that after death comes rebirth, and new blooms in time. Life on earth is, if nothing else, time. It is what we do with our time that will impact those after us. Like the flower, we have our hour, our time of beauty and then we too will pass. The question is: what high beauty, laughter and joy, or tragedy will come with our passing through? Will the audience in the future experience catharsis and pleasure when our act is done?

In the drama of life we, humanity, are both the protagonist and the antagonist. We are perpetually in conflict, but history gives us perspective and clarity and helps us see and learn from the past. Through hind-sight we are able to see the comedic and tragic stories of people making decisions in time. We see their hour in history, and through theirs, we try to make sense of our own. Like a perennial flower, humanity continues generation after generation. We will bloom again as time marches on. Therefore, we should weigh our decisions with good humor, knowing that with each solved problem comes a new one, but with it, a new generation for that hour. We must recognize that while we have great technology and minds to innovate, we are not Gods, we are temporary and can only use the tools and information available to us. Perpetually fixing problems that we create is not wise, but operating with humility and wisdom on the front end and using foresight will help us in our struggles to live ethical and responsible lives. Protecting life might be a good place to start; connecting to people and places through story might be another. Whether trying to save the planet or save souls, it is the intricacy of life, the good and the bad, that we are working out.

When it comes to the environmental narrative, the conflict is largely man against man. Our needs and wants conflict with our morals and duty to the greater community in which we belong. An inner story is played out in the heart and mind which shapes worldviews and determines actions. If we do not check our inner story against the larger story of life and look for the humorous, recognizing that true humor is laughter at oneself and true humanity is knowledge of oneself, we will lean toward the tragic and the vicious cycle will begin again. The virtue of humor is that it strikes at self-righteousness and produces humility that opens us up to more faith, and deeper belief and understanding. Humor is a sort of redemption in that we recognize that finality is the only real tragedy, but often what appears to be gone is just transformed into something new. The death of a flower is only a tragedy if it is never reborn, if it is gone forever. But there is a sort of joy that comes with the seasonal death of the flower because it invokes a longing in us as we recall it and know it will return. This awareness of nature results in renewal, restoration, and a sense of being grounded to something real and solid. The same is true of lost technology for new technology, lost employment for new opportunities and the discovery of new ways of life. The transition is often painful, but worth it in the long run. There is a certain hope that comes with the transitory because it alone holds the promise of change, growth, or improvement. The hope comes from knowing that we do not live in a static and unchangeable world. Though we may not think this deeply of the life and death of the flower, we sense it, feel it, and if we do think about it, we see the passing of time and our own life in it. As William Blake might surmise, we experience heaven, or a lifetime, in a flower.

If we can find joy in the death and rebirth of a flower, then we can certainly see the tragedy in the flowers total extinction. While we cling to our own mortality and work it out through our own inner narratives, we must be aware that life continues after us and like ripples in water, our short existence plays out long after we are gone. Like the flower, we too need sunlight, water, nutrients, and the right environment to thrive, but unlike the flower, we are not benign, we have choice and the ability to change and impact our environment. We have changed and manipulated the most intricate details of living things, including flowers, all the way to landscapes and oceans. Our fingerprints are on everything, whether intentional or unintentional. We have been able to breed, cross breed, and graft plants in order to make them common and available, to patent for profit, and to manipulate and change for enhanced genetic traits, but the original is worth much more than any reproduction. We have learned that our tampering has far reaching consequences. Land change brings with it invasive plants that choke out native plants; removing forests changes the microclimate, impacts the animals, the soil, and the air. Through landscape or ecological restoration people are now trying to get back to the original, to the landscape before humans altered it. Brownfields, urban or industrial centers, are being restored to greenfields in an attempt to restore the land. While there is some question as to which point in time to restore a landscape due to the difficulty and uncertainty in identifying the original state, it is an attempt to get back to the original. But for the most part, once an original is gone, it’s gone. Though we are trying to fix what we ruined or changed, there is no creating a species out of thin air. We cannot make a flower ex nihilo, we can only take what already exists and create with it. As manipulators, tinkerers, movers, shapers, destroyers, and storytellers, we have a moral obligation to consider our actions with what we are unable to make: the original.

If science is knowing, and art is doing, as Wendell Berry states, then certainly the process of environmental stewardship done well is the art of science in practice. Weaving many stories into the environmental narrative holds the most promise in ensuring that science is not void of compassion and values, and that people are not void of the knowledge that science provides. Otherwise, the single, narrow story will continue to be held, ensuring that an incomplete view and narrative is maintained. The narratives are what must be examined because they act as a the filter through which we view the world, make decisions, pass judgment, and ultimately, interact with each other. But they also hold possibilities to see new stories and expand our narrative paradigm. We are all human after all. We can relate to others through story, experiences, and values, but not facts. The narratives can act as the bridge between the process of decision making and the reality of those living with the decision.

Though the process of science is supposed to be objective, often the people impacted by it are not and the subjective interpretation is what determines the discourse, compromise, and/or gridlock over such cases. The narratives and philosophies behind the people meeting to shape such environmental decisions lie beneath the surface. The objective analysis the stakeholders are meant to examine and engage in is limiting and will either reinforce or reshape already held narratives through the process. When the process cuts values out of the equation, it removes compassion for the particular creatures, people, and place in question. Without this compassion, the species at hand gets pitted against the people impacted. Because the beliefs, values, and morals are determined by many factors not easily defined or standardized by the government, the decision must be based on evidence and sound arguments that can be applied equitably and broadly. This makes sense from a policy perspective, but not an empathetic or understanding one. Life is complicated and messy, decisions are not easily made, but that is where there needs to be room for the non-scientific, non-economic, or non-concrete. The inherent value of the plant and the inherent value of tradition and way of life, while not openly discussed, are there. Those values should be included in the narrative of environmental stewardship because they are the threads that hold the community together in the first place.

Perhaps we need to get to know our own place and community and weave our own story into it so that we can empathize with other places and people. I know that not everyone loves the desert the way that I do, but I am certain they love some geographical location somewhere in the world to the same degree. Stories of people and place fill volumes of literature that inspire and leave lasting imprints in the minds of people in all walks of life and from all corners of the world. It is time for story, normally relegated to classrooms, bookshelves, and coffee shops, used for study or leisure, to fill in the gaps between science and humanity, policy and citizens, and from person to person.

Red Rocks, NV, photo courtesy of puzzler4879 @ http://www.flickr.com

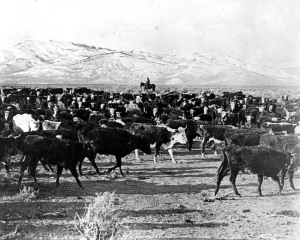

Free Grazing & Law Breaking: Cliven Bundy’s Stand against the Government

Here in America, we love our outlaws. We idolize them, romanticize them, and keep them alive in songs, folklore, stories, and movies. What is it that is so alluring about them? Perhaps it is for how they are remembered in myth as being Robin Hood type figures. Or maybe it is their bravado to stick a finger in the eye of the government, their courage and daring against all odds, or even their arrogance to attempt such feats that captures our imagination, but history remembers them differently. Outlaws were often murderers, thieves, gamblers, and criminals who did very little for the common or local folk. While they might be charming in movies and we can admire them from afar, none of us likes a law breaker. We all inherently understand this when we are the victim of law breakers, even when the crime is as slight as someone cutting in front of us in line, or getting free grazing when everyone else has to pay. They go against the grain of civil society, they break the rules and while they may have stamina, may be fighters, and may even stand on principle, at the end of the day, they are still law breakers.

In a small corner of Nevada in the little town of Bunkerville, a modern day outlaw is waging his own war against the government. Cliven Bundy is a rancher born into a long line of Mormon ranchers who settled along the Virgin River. According to him, his family has been ranching in Bunkerville for 130 years. I have met his relatives Orvel and Clay Bundy and they are good, solid, hard-working people. I was particularly impressed with Orvel when I met and talked with him in 2012. When I asked him about Cliven he replied, “A man’s got to make a living.” He let that phrase hang in the air. I know that Orvel has had his own battles with the BLM. As land management and stakeholders go, it is par for the course, but he has found a way to work within the limits of the law. Cliven, on the other hand, has taken a different approach working outside of the law, and now the Pied Piper has come to collect. As Mattie Ross said in True Grit, “You must pay for everything in this world one way or another.”

Some mistakenly believe that this is an environmental issue, or a liberty issue, or a property rights issue, but the facts will reveal that it is a legal issue. Cliven Bundy has been illegally grazing his cattle on federal land and not paying his grazing fees for nearly 20 years. Around 1993 the BLM started revising grazing permits to provide for the protection of the desert tortoise. Mr. Bundy didn’t like the change and so he stopped paying his grazing fees. It was at the moment that he stopped paying his fees that he gave up any legal standing he had to graze on public lands or to seek compensation. In response, the BLM cancelled his permit and would no longer grant him anymore grazing permits on BLM land. Around that time, there was a land swap between Nevada and the Federal Government where Nevada offered to buy the grazing allotments to set up a preserve to protect the desert tortoise in exchange for desert tortoise habitat that they could destroy for development. At the time, all ranchers who had allotments in the area were offered the chance to sell their allotments and did to the tune of roughly $5 million dollars. Mr. Bundy was not given the option of a buy-out for his allotment because he had forfeited his rights to it when he stopped paying his fees. Therefore, the permit was sold to Nevada for $375,000.00. Mr. Bundy now claims they are taking away his right to make a living, but as will be shown, he forfeited it all on his own.

When the United States was promoting westward expansion and homesteading, the lands were quickly over-grazed due to a lack of understanding of the arid west’s fragile ecosystem. According to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, “After decades of rangeland deterioration, conflicts between cattle ranchers and migratory sheepherders, jurisdictional disputes, and states’ rights debates – and in response to the pleas of western ranchers, Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 which effectively ended free access to the range.”

What was happening in the West prior to the Taylor Grazing Act was an economic theory coined the Tragedy of the Commons. It states that individuals acting independently and rationally according to each one’s self-interest, behave contrary to the whole group’s long-term best interests by depleting the common or shared resource. In other words, when a common good is “free,” people will selfishly use it until it is gone because they cannot self regulate, and those who try, quickly give up when no one else does. Regulating grazing ensured that the vegetation would regenerate and continue to provide productive land, further ensuring that grazing would continue into the future.

The purpose of the act was to stop injury to the public lands; provide for their orderly use, improvement, and development; and stabilize the livestock industry dependent on the public range. The new law effectively closed the rangelands to homesteading. The act established grazing districts on the vacant, unappropriated and unreserved lands of the public domain and established grazing advisory boards, primarily composed of livestock owners. Board duties included the allocation of permits and the determination of boundaries, seasons of use, and the carrying capacity of the range (1).

The new permit system granted grazing privileges (not rights) by preference to ranchers who had actually used a grazing district’s land during a priority period before 1934. Owners of land or water rights who could support livestock on base ranches during seasons when herds were not on the grazing districts were favored; those without property were not. Technically, the grazing permit is a revocable license under the law, not creating any right, title, interest, or estate in or to the land. The act also created the Grazing Service, but inadequate funding prevented effective observation and evaluation of range use partly because grazing fees were never raised to adequately fund the Service. Permitted animal unit months were set at preexisting 1934 stock levels. Efforts to reduce stock levels inevitably failed. The Grazing Service and General Land Office were then consolidated in 1946 to form the Bureau of Land Management (1).

According to the BLM, “The unregulated grazing that took place before enactment of the Taylor Grazing Act caused unintended damage to soil, plants, streams, and springs. As a result, grazing management was initially designed to increase productivity and reduce soil erosion by controlling grazing through both fencing and water projects and by conducting forage surveys to balance forage demands with the land’s productivity (“carrying capacity”). These initial improvements in livestock management, which arrested the degradation of public rangelands while improving watersheds, were appropriate for the times. But by the 1960s and 1970s, public appreciation for public lands and expectations for their management rose to a new level, as made clear by congressional passage of such laws as the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976. Consequently, the BLM moved from managing grazing in general to better management or protection of specific rangeland resources, such as riparian areas, threatened and endangered species, sensitive plant species, and cultural or historical objects. Consistent with this enhanced role, the Bureau developed or modified the terms and conditions of grazing permits and leases and implemented new range improvement projects to address these specific resource issues, promoting continued improvement of public rangeland conditions (2).”

As stated above, grazing permits do not equate to grazing or property rights and must be weighed in light of new laws, competing interests for present and future generations, and can be altered and/or revoked in lieu of changing circumstances. Those changing circumstances came in the early 1990s when the desert tortoise was listed as endangered. In response, the BLM modified Cliven Bundy’s Bunkerville allotment to protect the tortoise. As you will remember, along with the Taylor Grazing Act, the BLM is also beholden to the Endangered Species Act. By law, they are required to protect species, as well as manage grazing allotments. They were doing their job. Mr. Bundy, however, didn’t like the grazing permit change and rejected the new grazing permit on grounds that he did not recognize the law or the legal authority of the BLM to change the permit. He stopped paying his grazing fees and continued to allow his cattle to not only graze on the Bunkerville allotment, but allowed them to graze on federal land as far as the Lake Mead Recreation Area.

According to the BLM Northeast Clark County Cattle Trespass timeline, in 1997, in accordance with the Desert Tortoise Recovery Plan and the Biological Opinion released by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, active grazing permits in tortoise habitat were purchased by Clark County under the Clark County Multi-Species Habitat Conservation Program. Mr. Bundy rejected a tentative proposal to compensate him for any stockwater rights or range improvements he might have in his former allotment. It should be noted that all other ranchers who grazed in the Bunkerville allotment did accept the compensation and have been complying with federal law and the agencies enforcing it and are actually supporting the BLM. He is the only one defiantly disobeying the law. Not only it is not fair to the public, it is not fair to ranchers who are paying their fees and abiding by the law. In 1998, the United States filed a civil complaint against Mr. Bundy for his continued trespass grazing in the Bunkerville Allotment. The U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada issued an order permanently enjoining Mr. Bundy from grazing cattle on the Bunkerville allotment, ordered him to remove all trespass cattle and set a penalty of $200 per day per animal remaining on the federal range (4).

Mr. Bundy has insanely, arrogantly, or in a willful attempt at wishful thinking charged in federal court that the land was not federal land, wherein the court disagreed stating, “the public lands in Nevada are the property of the United States because the United States has held title to those public lands since 1848, when Mexico ceded the land to the United States (5). In 1999, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the District Court’s permanent injunction. When Mr. Bundy failed to remove his livestock as directed by the District Court, the United States filed a motion to enforce the permanent injunction and the District Court ordered Mr. Bundy to pay $1,377 as willful repeated trespass damages and adjusted fines to be consistent with regulatory rates of $45.90 per day for each day Mr. Bundy’s cattle remained on the allotment (4).

In 1999, the Las Vegas Field Office Resource Management Plan designated the Bunkerville allotment as “Closed to Grazing” to protect desert tortoise habitat.

In 2008, the BLM issued a decision to cancel Mr. Bundy’s range improvement authorizations (one range improvement permit and ten cooperative agreements). Mr. Bundy submitted a letter objecting to the action which BLM forwarded to the Interior Board of Land Appeals (IBLA) as an appeal. The IBLA issued a decision affirming the BLM’s cancellation decision on December 22, 2008. In 2011, BLM issued Mr. Bundy a Trespass Notice and Order to Cease and Desist, a Trespass Decision and Order to Remove, and a Notice of Intent to Impound. None of these communications resulted in Mr. Bundy’s voluntary removal of the trespass cattle from the public lands (4).

In May 2012, the United States filed a Complaint seeking declaratory and injunctive relief for Cliven Bundy’s trespass grazing within the Gold Butte area outside the Bunkerville Allotment, including within Lake Mead National Recreation Area. In April 2013, the United States filed a Motion to Enforce the 1998 Permanent Injunction against Cliven Bundy for the Bunkerville Allotment. On July 9, 2013, U.S. District Court of Nevada Judge Lloyd George permanently enjoined Cliven Bundy’s trespass grazing and ordered Cliven Bundy to remove his trespass cattle from public land outside the former Bunkerville Allotment within 45 days, stating that the United States is authorized to seize and impound any cattle that remain in trespass after 45 days. On October 9, 2013, U.S. District Court of Nevada Judge Larry Hicks reiterated that Cliven Bundy is permanently enjoined from grazing the Bunkerville Allotment and has no legal right to graze the federal lands, directed him to remove his trespass cattle from the former Bunkerville Allotment within 45 days, authorized the United States to impound his cattle if he fails to remove them within 45 days or continues to trespass at a future date and directed Mr. Bundy not to physically interfere with an impoundment action (4).

As can be seen, Mr. Bundy has been willfully and arrogantly breaking the law for 20 years. The BLM, the State of Nevada, and the courts have been more than civil and patient, exhausting all legal options trying to do their jobs, to enforce the law, and to resolve the problem peacefully. How Mr. Bundy has been able to ignore and bully not only state but federal agencies is beyond me. It was obviously baffling enough to the Center for Biological Diversity that in April 2012 they filed a 60 day notice of intent to sue the BLM for not doing their job under the Endangered Species Act (6). Now Cliven Bundy is playing the victim, stating that because his family has been ranching and grazing cattle there for 100 or more years, on land that is not his, he is somehow entitled to continue. His stance is not only groundless legally, it is selfish. This one man wrongly believes that his rights supersede the rights of the public and are above the law. But it’s worse than just grazing for free, Mr. Bundy has been grazing his cattle at the public’s expense.

Summer Camps & Education, Wilderness & Open Space Preservation, and Energy Development on Public Lands

We pay tax dollars to have our public lands managed, to have equal access under the law, and to have the law enforced. Mr. Bundy has made his right to graze his cattle more important than all other interests. According to Mary Jo Rugwell, who used to be the BLM Southern Nevada District Manager, “There are hundreds of ranchers that follow the rules. They have grazing permits, pay their fees and manage their cattle as they are supposed to. A lot of other users of public lands also pay for permits and follow their stipulations. It’s just not fair to all of those people that Mr. Bundy does what he wants and doesn’t follow the rules (7).” He, and others like him or supporting him, may not like the Endangered Species Act and may not like federal law or control, but not liking something does not excuse one from breaking the law. Furthermore, not believing in laws does not make them any less real, valid, or enforced. One does not change the law by breaking the law.

Mr. Bundy claims he will do whatever it takes to protect his life, liberty, and property, but none of those things would be in danger if he had actually done the one thing that would have guaranteed them: obeying the law. Clearly he was not willing to do anything. What Mr. Bundy wants is to have his cake and eat it too.

Outlaws are not victims. They are people who have chosen to go outside of the law, to claim that the law does not apply to them, and then seek support and favor from their local community when they are finally challenged and claim that they are fighting for everyone. Many famous outlaws have made such claims and gone down in myth and lore as being for the little guy or for their local communities, but history notes it differently. These were men and women who chose to break the law, not for others, but for their own selfish ends. Though we may be enamored with characters that seem to capture the essence of the wild west, we must remember that this is no longer the wild west and that they were or are outlaws, not victims. Before anyone mistakenly thinks I am comparing Mr. Bundy to those famous outlaws, I will state that the comparison ends at breaking the law. That being said, in an interview with the Moapa Valley Progress, Bundy said that he was “willing to defend his rights at all costs.” When asked whether the matter might come to violence he said, “Why not? I’ve got to protect my property. I have a right to life, liberty and property (7).” I will let you decide how similar he is to outlaws of the past.

While this is an emotional issue for many who know and like Mr. Bundy, at the end of the day, he brought this on himself. If he is a victim of anything, he is a victim of his own arrogance. He willfully broke the law and chose not to work within the confines and limits of it. He has gotten away with it for 20 years. It is time for the BLM to call his bluff and end his free grazing and law breaking now. If he wants to sue Clark County, the state of Nevada, the BLM, the cowboys who will be rounding up his cattle, or anyone else, let him do it. He does not have a case, as has been shown. His argument is weak at best, and absurd at the worst. As the court order states,

“Bundy has produced no valid law or specific facts raising a genuine issue of fact regarding federal ownership or management of public lands in Nevada, or that his cattle have not trespassed on the New Trespass Lands. The United States has established irreparable harm not only through the continuing nature of Bundy’s trespass, but because Bundy’s cattle have caused and continue to cause damage to natural and cultural resources and pose a threat to public safety. The public interest is best served by removal of trespassing cattle that cause harm to natural and cultural resources or pose a threat to the health and safety of members of the public who use the federal lands for recreation. The court finds that the public interest is negatively affected by Bundy’s continuing trespass. Finally, the public interest is served by the enforcement of Congress’ mandate for management of the public rangelands, and by having federal laws and regulations applied to all citizens equally (5).”

The BLM is not the bogeyman. It is not a nameless, faceless organization out to get one man. It is an agency filled with average, everyday people trying to do their job, and managing land for competing interests is a hard one at that. Mr. Bundy has had more than ample time to resolve this issue amicably and reasonably, it is time that he suffer the consequences that anyone else would who blatantly breaks the law. That he is seeking public support on emotional grounds here in southern Utah speaks to his lack of a case. He does not deserve our sympathy; he deserves a reality check that has been a long time coming.

Citations:

(1) Encyclopedia of The Great Plains: http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ag.071

(2) BLM Grazing: http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/grazing.html

(3) BLM Mission: http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/grazing.html

(4) BLM History of Trespass Cattle: http://www.blm.gov/nv/st/en/fo/lvfo/blm_programs/more/trespass_cattle/history_of_trepass.html

(5) Court Orders July 9th & October 9th, 2013: http://www.blm.gov/nv/st/en/fo/lvfo/blm_programs/more/trespass_cattle/court_orders.html

(6) Center for Biological Diversity, Intent to Sue: http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/reptiles/desert_tortoise/pdfs/60_day_notice_to_BLM_FWS__HCP_BP_IA.pdf

(7) Moapa Valley Progress, Bunkerville Rancher Holds out against Federal Officials: http://mvprogress.com/2012/04/18/bunkerville-rancher-holds-out-against-federal-officials/

(8) The Spectrum Daily News, Bundy Saddles Up: http://www.thespectrum.com/viewart/20140313/DVTONLINE01/303130030/Mesquite

(9) Las Vegas Review Journal, Emotions Run High as BLM closes 600,000 acres for cattle roundup: http://www.reviewjournal.com/news/emotions-run-high-blm-closes-600000-acres-cattle-roundup