Blog Archives

The BLM, Ranchers, and Domestic Terrorism Part II: Prosecution, Terrorism, and Equality under the law

“We all hold the keys to our own jail cells.”

― Paul Levine, Soloman vs. Lord

***For comparable arson cases see HCN arson link below***

Before diving into the Anti-terrorism and death penalty Act or terrorism generally, a brief discussion of how and why a U.S. Attorney will prosecute someone is necessary. U.S. prosecutors have broad discretion when it comes to prosecuting someone of a federal crime. They also have broad discretion in deciding which laws to prosecute under. That being said, there is a litmus test to determine if they should prosecute in the first place.

According to the United States Department of Justice, Offices of U.S. Attorneys, there are Principles of Federal Prosecution, the purpose of which is to assist in structuring the decision-making process of attorneys for the government. The principles serve the purpose of “ensuring the fair and effective exercise of prosecutorial responsibility by attorneys for the government, and promoting confidence on the part of the public and individual defendants that important prosecutorial decisions will be made rationally and objectively on the merits of each case.”

A determination to prosecute represents a policy judgment that the fundamental interests of society require the application of the criminal laws to a particular set of circumstances—recognizing both that serious violations of Federal law must be prosecuted, and that prosecution entails profound consequences for the accused and the family of the accused whether or not a conviction ultimately results.

A prosecutor has wide latitude in determining when, whom, how, and even whether to prosecute someone for apparent violations of Federal criminal law. Attorneys exercise prosecutorial discretion for the government with respect to:

- Initiating and declining prosecution;

- Selecting charges;

- Entering into plea agreements;

- Opposing offers to plead nolo contendere;

- Entering into non-prosecution agreements in return for cooperation; and

- Participating in sentencing.

When an attorney is deciding whether or not to prosecute there are some things to consider. If the attorney for the government has probable cause to believe that a person has committed a Federal offense within his/her jurisdiction, he/she should consider whether to:

- Request or conduct further investigation;

- Commence or recommend prosecution;

- Decline prosecution and refer the matter for prosecutorial consideration in another jurisdiction;

- Decline prosecution and initiate or recommend pretrial diversion or other non-criminal disposition; or

- Decline prosecution without taking other action.

The attorney for the government should commence or recommend Federal prosecution if he/she believes that the person’s conduct constitutes a Federal offense and that the admissible evidence will probably be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction. But even further than that, they must determine if a substantial Federal interest would be served by prosecution. In order to determine if prosecution should be pursued or declined, the attorney for the government should weigh all relevant considerations, including:

- Federal law enforcement priorities;

- The nature and seriousness of the offense;

- The deterrent effect of prosecution;

- The person’s culpability in connection with the offense;

- The person’s history with respect to criminal activity;

- The person’s willingness to cooperate in the investigation or prosecution of others; and

- The probable sentence or other consequences if the person is convicted.

In the case of Dwight and Steven Hammond, their actions clearly fell into federal jurisdiction. One can assume that U.S. Attorney Amanda Marshall, who chose to prosecute the Hammonds, did so because she believed it was in the interest of the United States to do so. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assert that she believed the seriousness of the offense warranted the prosecution, that she believed the prosecution would deter others from committing similar acts, and that the Hammond’s’ culpability and prior “criminal” activity required prosecutorial action. While this is just speculation, Marshall may have chosen to prosecute under the anti-terrorism law to get the minimum mandatory sentence and make an example out of them.

Marshall had this to say after their conviction, “Fires intentionally set on public lands endanger firefighters and the public. The verdict sends an important message to those who think that they are above the law.”

It’s the “thinking they are above the law” part that leads one to conclude that was why she chose to prosecute them. Furthermore, anyone who accidentally ignites a fire on public lands will be given a bill from the managing land agency, so it stands to reason that citations and damages would in the very least be sought in intentional cases of arson.

But back to the prosecution, in light of and in comparison to the Cliven Bundy (Bunkerville) situation, which happened simultaneously, Marshall’s reasoning is not outrageous or irrational. When prosecutors quickly go after city law breakers, but do not go after rural law breakers, it gives the impression that some get preferential treatment under the law. The impression that what is good for one group is not necessarily good for another group is problematic in that it shows either favoritism or discrimination under the law.

This discrepancy in the enforcement of the law reveals inequality in the application and enforcement of it. If someone can have their license revoked for reckless driving or speeding, certainly a person can have their grazing rights revoked for repeated trespass cattle, igniting wild fires, and/or open disregard for laws and regulations.

As for which law(s) a person/people can be tried under, again, that is up to the discretion of the prosecutor. In this case, U.S. Attorney Amanda Marshall charged the Hammonds under the Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. While at first blush this law seems an extreme one to prosecute ranchers under, if their actions could be found consistent with those outlined under terrorism in the U.S. criminal code, then it was an option. No case is a slam dunk. Marshall clearly believed that the case, evidence, and testimonies would be compelling enough that the jury would find them guilty of arson under the anti-terrorism law. Based on the partial verdict, she must have made a strong case with the arson charges.

The Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 came after the attack on the World Trade Center and the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building. Analyzing this law is beyond the scope of this article, but arson is listed in Sec. 708. Enhanced penalties for use of explosives or arson crimes. To read the act click here.

Terrorism is a buzz word used a lot today and is one that is taken very seriously. In order to really understand how someone can be prosecuted as a terrorist, one must understand the legal definition of it. According to the FBI’s website, 18 U.S.C. § 2331 defines “international terrorism” and “domestic terrorism” for purposes of Chapter 113B of the Code, entitled “Terrorism.” For the purposes of this article only domestic terrorism will be shown.

“Domestic terrorism” means activities with the following three characteristics:

- Involve acts dangerous to human life that violate federal or state law;

- Appear intended (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination. or kidnapping; and

- Occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the U.S.

18 U.S.C. § 2332b defines the term “federal crime of terrorism” as an offense that:

- Is calculated to influence or affect the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion, or to retaliate against government conduct; and

- Is a violation of one of several listed statutes, including § 930(c) (relating to killing or attempted killing during an attack on a federal facility with a dangerous weapon); and § 1114 (relating to killing or attempted killing of officers and employees of the U.S.).

When one looks at what the Hammonds’ were charged with, while it may seem a stretch, one can see how the case could be made. Marshall produced evidence that the Hammonds’ willfully destroyed government property, that their fires did put people at risk, and while it is unknown if she asserted this, that their actions reveal that because they were tired of waiting on the BLM to do prescribed burns or pest control for weeds on their allotment, their decision to burn the land could be perceived as trying to influence or affect the policies or conduct of the government via intimidation, coercion, or retaliation – especially in light of their criminal history with federal employees.

What is to be seen, however, is whether this law will be applied in Nevada toward the Bundys. While I am certain that the cumulative actions of the Hammonds’ led to their prosecution and subsequent conviction, it seems to me that what the Bundys’ did in Bunkerville was much closer to domestic terrorism than what the Hammond’s did, which begs the question: What is U.S. Attorney Daniel G. Bogden (Nevada) doing and why has he seemingly done nothing?

It’s not just the history of Cliven Bundy not paying his grazing fees, allowing trespass cattle to graze where they are not allowed, or the fact that he has been handily beaten in court that is of concern; it’s the open rebellion and subtle or outright threats against not just the government or government agencies, but threats against individuals, that puts him, his family, and his supporters in a different category. This category being much closer to eco-terroristism than American heroism. In fact, on the Bundy’s blog, they have issued subtle threats in response to the Hammond case as recently as November 3, 2015.

When federal employees are getting death threats, when they get run or chased down on public land and are threatened or harassed, or are targets of rural mobs threatening gun violence, whether they are ranchers, gangs, or militias, such acts are crimes that “terrorize” people. This applies to verbal or written threats as well. While Dwight Hammond was never charged for making death threats, nor were his supporters, and the Bundys’ have not been charged with making threats either, one could make the case that both engaged in threating behavior.

According to the legal definition, a terroristic threat is a crime generally involving a threat to commit violence communicated with the intent to terrorize another, to cause evacuation of a building, or to cause serious public inconvenience, in reckless disregard of the risk of causing such terror or inconvenience. It may mean an offense against property or involving danger to another person that may include but is not limited to recklessly endangering another person, harassment, stalking, ethnic intimidation, and criminal mischief.

In the Bundy case, they clearly threatened to commit violence, to cause serious public inconvenience, and did so with disregard for the risks. Their actions did involve property and danger to people.

The following is an example of a Texas statute dealing with terroristic threats:

TERRORISTIC THREAT

(a) A person commits an offense if he threatens to commit any offense involving violence to any person or property with intent to:

- cause a reaction of any type to his threat[s] by an official or volunteer agency organized to deal with emergencies;

- place any person in fear of imminent serious bodily injury;

- prevent or interrupt the occupation or use of a building; room; place of assembly; place to which the public has access; place of employment or occupation; aircraft, automobile, or other form of conveyance; or other public place;

- cause impairment or interruption of public communications, public transportation, public water, gas, or power supply or other public service;

- place the public or a substantial group of the public in fear of serious bodily injury; or

- influence the conduct or activities of a branch or agency of the federal government, the state, or a political subdivision of the state.

The legal definition of “terrorist threats” in Las Vegas, Nevada, makes it unlawful to issue any threat concerning an act of terrorism with the intent to:

- injure, intimidate or alarm any person, or

- cause panic or civil unrest, or

- extort or profit, or

- interfere with the operations of or cause economic or other damage to any person or any officer, agency, board, bureau, commission, department, division or other unit of federal, state or local government

It doesn’t matter whether the terrorist threat actually resulted in any harm. Merely communicating a threat with the intent to cause injury, panic, profit or destruction qualifies as criminal activity.

The Bundys and their mob not only threatened, they acted on the threats. Cliven Bundy’s 20 years of law breaking was compounded further when he engaged in what could be considered terroristic threats and domestic terrorism in the face of having to suffer the consequences for those 20 years of breaking the law.

Furthermore, everyone else who showed up to support him by doing the same is also guilty. Surely raising an armed rebellion causes terror, not just for those present, but for federal employees trying to do their jobs and the public at large who may pass through such areas where open rebellion exists; and clearly Bundy profits from being able to graze (make a living) without paying the required permit fees.

If one looks at the above definition of terroristic threats, it is not hard to see how the Bundys have engaged in many of those listed.

As for the U.S. Attorney in Nevada, Daniel G. Bogden, and the U.S. Justice system, not only does it serve the federal interest to prosecute the Bundys, but their prosecution, like the Hammonds’, should be pursued as a deterrent for other would-be law breakers who may be encouraged and emboldened by the lack of consequences in the Bundy case (such as the Cane Beds, AZ man who after spending time with the Bundys and attending the Bunkerville standoff decided to stop paying his grazing fees and let his cattle graze where they shouldn’t).

There cannot be separate consequences, or no consequences, for those in rural areas when there are for those in urban areas. Terrorizing in a rural setting is no different than terrorizing in an urban settings and should be treated the same way.

For far too long rural western violence has gone unpunished (see The Shovel Rebellion). Ranchers and cowboys no longer live far away from civilized institutions or the law.

Obviously not all ranchers are like the Hammonds or the Bundys, and in fact, most pay their grazing fees and work out their differences with land management agencies civilly. But while no one wants to blame all ranchers for the few wreaking havoc (its always the few bad apples that make the whole group look bad), it is hard not to wonder about the general attitudes of the whole when so many come to the aid of people like the Hammonds and the Bundys, or take it a step further by threatening authorities. We cannot say out of one side of our mouths that law breakers should be punished, such as rioters in inner cities, and then defend law breakers in rural towns.

In this case it appears that Oregon was determined to deal with the problem, unlike Nevada. But on a federal level, it looks bad for ranchers in one state to get charged when ranchers in another do not. If the anti-terrorism law is going to be applied in Oregon, it stands to reason that the same law should, or at least the same level of law enforcement, should be applied across all states.

If ranchers are angry about laws, rules, and regulations, they need to do what everyone else has to do: either work to change legislation and/or create new legislation, or engage in civil disobedience by breaking the law, but acquiesce to suffer the penalties under the law.

Everyone gets frustrated with the government, or laws. Everyone wants a fair shake. In regard to ranchers, most people are fair in their attitudes toward ranching and either support it or grudging support it on public land because it is allowed.

What people don’t understand and won’t support is wanton breaking of the law at the expense of everyone and everything else. Breaking the law and then suggesting you shouldn’t be punished is exactly what U.S. Attorney Amanda Marshall described as thinking you are above the law. No one is above the law.

MOVING FORWARD

It terms of land management, it may be time to put pressure on Congress to increase budgets for land management agencies so that they can hire adequate staffing to manage the land appropriately and efficiently. When Congress plays politics with public lands and cuts budgets, it slows the agencies down and inhibits them from doing such things as prescribed burns or environmental impact statements in a timely manner.

It may also be time to rethink the price of grazing on public lands. It’s probably time to either let the market decide the price or charge what ever the state charges within its boundaries.

When the west was being settled, the U.S. government tried to get ranchers to homestead by giving them land, but the ranchers didn’t want to own the land because leasing it/grazing permits were cheaper (Donahue 1999).

And again during the Hoover administration, the states and ranchers were given the opportunity to take the land, but the states did not want it because “the lands were perceived as having little value, and many of the stockgrowers feared the economic consequences of obtaining title to public domain grazing lands. They wanted use of the lands but not the expense or liability of ownership (Donahue, 1999).”

Our public lands are worth something – much more than the pittance they are charging for grazing today – and many are willing to pay for use and care of the land. Obviously the states place value on their lands by charging up to 10 or 20 times what the federal government does.

Beyond that, it’s time to educate ourselves on how the government works, what rights are and are not, and how the law works. Many today need to understand that in between the drafting of the constitution and now are all of the laws and legal precedent set by court cases that determine what is legal for both the government and the people. Laws can be disputed and weighed against the constitution, and can be challenged in court, but just because a law, regulation, or agency is not spelled out in the constitution does not mean it is unconstitutional.

In the case of the Bundys and the Hammonds, they and others have made rather ignorant claims about the authority of the United States Government, about local authority, about land management agencies’ authority, about grazing rights, and about individual rights in regard to public land.

Congress has been given the authority to control property owned by the federal government under the property clause of the constitution. They enact laws that give special authority as well as mandates to land management agencies for managing the land; laws and priorities for public land has changed over time and will probably continue to change. Nothing is static or set in stone.

Civil life is very dynamic and in a constant state of flux. Public land is not just managed for grazing. It is managed for wildlife, ecological health, recreation, science, preservation, and for future generations as required by the people of the United States via a representative form of government. Land management agencies are required by Congress, via the public, to consider all of the users, including wildlife, resources, and the land itself, in their decisions. One group does not get preferential treatment above all the rest.

Because someone’s family has been ranching on public land for 100 years does not necessarily mean they will get to ranch there until the end of time. Nor does having access without a permit mean you will never have to get one. Having a long history of grazing rights does not mean those rights are set in stone. Grazing rights are not property rights – they are more like a license that is given and can be revoked and the courts have consistently upheld this.

In the 1973 decision of United States v. Fuller, the United States Supreme Court continued existing precedent in the area of property rights. It held that a federal range permittee is not entitled to compensation for the taking of his permitted lands for another public use, nor is the permittee allowed additional compensation for the increased value of his fee lands as a result of the attachment of Taylor Act privileges.

The Court based its ruling on the facts that the permits are revocable by their terms and do not create a property right. In closing public lands to grazing except by permit and upholding trespass actions on public lands, the United States Supreme Court has held that, “The United States can prohibit absolutely or fix the terms on which its property may be used.”

I’m sure that all people of all industries would like to have their livelihoods guaranteed in perpetuity by the United States government, but it doesn’t work that way. Industries come and go. National priorities change. That is called capitalism and democracy. People lose their jobs and have to adapt all the time. Ranchers are no exception. If we don’t pay our property taxes, we lose our property. If ranchers don’t pay their grazing fees, they lose their right to graze. Family traditions and heritage are important, but you don’t sustain them by breaking the law.

While ranchers may have legitimate grievances and complaints with the government and land management agencies, breaking the law is not the way to go about changing things. Land management agencies have been given mandates for how to manage the lands and discretion with rules for ensuring those mandates are met.

In the case of the Hammonds, and using the wildlife refuge, they were given continued access by the Fish & Wildlife Service, who have the discretion to allow grazing or not, until they stopped abiding by the rules the FWS required for such access. It has been claimed that the Hammonds had water rights and that the FWS was restricting those water rights. However, the water was part of the refuge.

The “National Wildlife Refuge System” means all lands, water and interests therein administered by the FWS as wildlife refuges, wildlife management areas, waterfowl production areas, and other areas for the protection and conservation of fish and wildlife. Grazing is allowable only at the discretion of the FWS as mandated by the stated purpose of wildlife refuges: All national wildlife refuges are maintained for the primary purpose of developing a national program of wildlife and ecological conservation and rehabilitation. Therefore, grazing and other kinds of private economic uses may be, and commonly are, allowed on wildlife refuges. However, no public or private economic use is permissible if it is not compatible with the primary purpose of the refuge.

When the Hammonds’ stopped abiding by the rules required for the access through the refuge, it was within the rights and obligations of the FWS to fence the Hammonds’ cattle out and to limit their access. One can reasonably assume that had the Hammonds played by the rules they would still have access today.

In terms of igniting fires to improve their grazing allotment, that was also not within the rights of the Hammonds. Because they have burned on their own property does not mean they are trained wildland firefighters, authorized to burn on public land, and furthermore, because they have grazing rights does not mean they are the only users of that land.

Igniting a fire may, and did, improve the land for grazing, but the land is not just managed for grazing. Some are trying to make the case that because wildland firefighters ignite prescribed burns that often get out of control, the Hammond’s should not be charged with a crime for doing the same. This is fallacious thinking because it is not about the act itself, but about who is authorized to perform the action.

That being said, there is a striking difference between the Hammonds’ and the Bundys’ in that the Hammonds’ have accepted responsibility for their actions, acquiesced to the rule of law, and did not follow up the legal repercussions with open rebellion. It is to be seen, however, whether the Bundys will get involved in Oregon and change that.

In terms of the Bundys, their claims are varied and many, none of which have much merit. Most have been discussed here. But one issue has not and must be addressed and that is the issue of fencing.

Cliven Bundy tried to make the case that the local government was required to fence out his cattle. Others have claimed that the federal government was required to fence out his cattle. In terms of the federal government being required to fence out cattle, the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled against that idea.

In Shannon v. United States the Supreme Court stated that “the United States has the unlimited right to control the occupation of the public lands and is under no obligation to fence those lands, or to join with others in fencing them for the purpose of protecting its rights, nor can that be imposed on it by a State.”

Fence laws are state statutes meant to protect private property owners and which provide that damage done by domestic animals cannot be recovered unless the land (private) had been enclosed with a fence of the size and material necessary to restrain the animals. States may be required to fence out domestic animals on state lands, but they have no authority to fence out domestic animals on federal lands. Furthermore, in some cases individuals are required to fence in their own animals. These laws exist for civil defense against cattle or domestic animal owners who damage private property.

In Light v. United States, the Court, in dictum, stated: “Fence Laws do not authorize wanton and willful trespass, nor do they afford immunity to those who, in disregard of property rights, turn loose their cattle under circumstances showing they were intended to graze upon the lands of another.’” Judge Russell E. Smith ruled inter alia that the United States could not be compelled to fence its lands and went on to say that, “The requirement that persons fence their cattle out of federal lands though onerous, is legal.”

CONCLUSION

In the end, it is unfortunate for the Hammonds that they were convicted under this law, but it cannot be stated enough how significant this case is for the future of ranchers, land management agencies, and the public, to say nothing of the impact on public lands themselves. U.S. Attorney Marshall used her discretion to prosecute under the anti-terrorism law and won. Oregon is not playing around and any considering actions similar to the Hammonds’ will probably now think twice. This cannot be said for Nevada.

While there are unjust laws and people do get convicted unjustly under what seem to be “gotchya” laws, it cannot be over stated how this case could impact future actions on public lands. Using this law does seem a bit extreme, but in the context of the standoff in Bunkerville, it doesn’t seem as extreme as it does at first blush.

When people become emboldened to break the law because they have never had to face the consequences of breaking it, it is dangerous for everyone and sets a scary precedent that anyone can do anything if it serves their own interests. Not only does this case set a precedent for others who commit similar acts, it reveals how valuable our public lands are, that just because they are not a building does not mean they are not still United States property, and that one group of users does not get preferential treatment or access to it over all others.

Because more and more people are becoming aware of the ecological impacts of grazing, as well as the recreational, environmental, and scientific opportunities on our public lands, ranchers who do not abide by the law will continue to find themselves in the public eye.

Furthermore, those in the justice and legal systems who do nothing to rural violators, but go after urban violators, will also come under increased scrutiny. The law must be applied consistently and equally across the board or there will continue to be civil unrest and legitimate grievances by those who face the penalties of the law when others do not. Furthermore, unequal prosecution, like water that freezes and breaks apart rocks, will erode the faith people have in our legal and justice systems, which is already pretty battered, and it will undermine the legitimacy of the rule of law that is the foundation of our society.

Disclaimer: I am wary of all encompassing “gotchya” laws passed by perhaps a well-intentioned, if not overly zealous Congress that could turn every man, woman, and child into a criminal and I believe we must be vigilant in keeping an eye on what Congress does and work to kill or undo such laws. Giving up our rights or liberties for security is not wise. Furthermore, I take issue with prosecutors who zealously and unjustly go after individuals to make a name or career for themselves. When first reading about this case I thought it was one where people should be righteously upset with the government in defense of a rancher and hoped to use it as a counter example to the Bundys. Upon researching the case deeper, however, I found that the Hammonds were not unlike the Bundys and found their conviction to be reasonable, even if the word “terrorist” is a bit shocking. A person can be a rancher and a terrorist just like a scientist, environmentalist, school teacher, or student can also be a terrorist. It is the actions they commit that put them into that category and that earns them that label. That being said, I don’t think the Hammond case is being framed in entirely the right light. They were charged with arson under an anti-terrorism law. Technically, that makes them arsonists. Using the word terrorist, however, certainly gains more attention, traction, and sympathy.

Update 1/11/2016 Note: Arson is no joke. I decided to look into other arson cases to see how they compared to the Hammond case and under what laws the arsonists were charged. I found a High Country News article which states that the Hammonds burned 45,000 acres over a 28 year period. Arson is a crime. It is an expensive and dangerous crime and it causes real damage. We the people foot the bill for it. It appears that the Hammonds could have been charged under different laws, and in this case from a PR perspective it might have been wiser to do so, and could have received equal prison sentences to what they received under the anti-terrorism law.

Sources:

Donahue, Deborah L. The Western Range Revisited, 1999. University of Oklahoma Press.

9th Circuit Court Decision: United State of America v. Steven Dwight Hammond and Dwight Lincoln Hammond: http://media.oregonlive.com/pacific-northwest-news/other/hammondopinion.pdf

Reporters transcripts of court proceedings, U.S. v. Dwight and Steven Hammond, http://landrights.org/or/Hammond/Transcript%20of%20Judges%20ruling.pdf

Recent Developments in the Law of livestock grazing on public lands, University of Montana, Public Land and Resource Law Review, http://scholarship.law.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=plrlr

Offices of the United States Attorneys, Principles of Federal Prosecution, http://www.justice.gov/usam/usam-9-27000-principles-federal-prosecution

The Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-104publ132/pdf/PLAW-104publ132.pdf

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Definition of terrorism in the U.S. Code, https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/terrorism/terrorism-definition

Terroristic threat law and legal definition, http://definitions.uslegal.com/t/terroristic-threat/

Ecology Law Quarterly, Clinton’s National Monuments: A Democrat’s Undemocratic Acts, http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1697&context=elq

High Country News, Ranchers arrested at wildlife refuge, http://www.hcn.org/issues/20/582

High Country News, Some notable arson wildfire cases in the west: http://www.hcn.org/issues/42.13/some-notable-arson-wildfires-in-the-west

The Oregonian, Oregon Live:

Eastern Oregon cattle ranchers plead not guilty to illegally setting rangeland fires, http://www.oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2012/05/eastern_oregon_cattle_ranchers.html

Eastern Oregon father-son ranchers convicted of lighting fires on federal land, http://www.oregonlive.com/pacific-northwest-news/index.ssf/2012/06/eastern_oregon_father-son_ranc.html

Harney County rancher and son sentenced too lightly for arson convictions, federal appeals panel says, http://www.oregonlive.com/pacific-northwest-news/index.ssf/2014/02/harney_county_rancher_and_son.html

Controversial Oregon ranchers in court Wednesday, likely headed back to prison in arson case, http://www.oregonlive.com/pacific-northwest-news/index.ssf/2015/10/controversial_oregon_ranchers.html

Western Livestock Journal, Hammonds’ range fire prosecution: a deeper look, https://wlj.net/article-permalink-11862.html

Oregon Public Broadcasting, Hammond witness describes setting fire in 2001, http://www.opb.org/news/article/hammond_witness_describes_setting_fire_in_2001/

Capitol Press, Judge sends Oregon ranchers back to prison, http://www.capitalpress.com/Oregon/20151007/judge-sends-oregon-ranchers-back-to-prison

Breitbart, The Saga of the Bundy Ranch – Federal power, rule of law and averting potential bloodshed, http://www.breitbart.com/big-government/2014/04/12/the-saga-of-bundy-ranch/

St. George News, Arizona rancher follows in Bundy’s footsteps, https://www.stgeorgeutah.com/news/archive/2015/11/01/mgk-finicum-blm-dispute-bundy/#.Vk_BBfmrTIV

Bundy Ranch Blog:

Facts and Events in the Hammond Case, http://bundyranch.blogspot.com/2015/11/facts-events-in-hammond-case.html

Hammond family declared as terrorist and sentenced to five years in federal prison, http://bundyranch.blogspot.com/2015/11/hammond-family-declared-as-terrorist.html

Shovels, Sagebrush, and Cattle: Nevada’s Rural Violence Problem

“Knowledge is a weapon Jon. Arm yourself well before you ride into battle.”

~ George R.R. Martin, A Feast for Crows

If the Cliven Bundy standoff has show us anything, it is that a strain of fringe, anti-federalists not only exist in the county, but are willing to act at the least provocation. The resort to violence by rural people in Nevada is not an anomaly and is not an isolated incident. The unrest, angst, and itch for violence against federal agents and employees is always there under the surface. This county has a long and inglorious history of such factions and groups, and though not limited to the West, they seem to be unduly present not only in rural communities but by leaders and politicians hankering to wrest control of public lands from the Federal Government. There were outcries over the BLM’s show of force in April toward the ranchers and militias, of their preparation for violence, but it will be shown that the BLM had good reason to come prepared. Their good faith effort in 2012 to round up Bundy’s cattle without weapons was called off due to violent threats, which as will be shown, have been real and acted upon in the past.

Anti-federalism groups, or Constitutional vigilantes, have a long and colorful history, beginning with the most notorious faction, the KKK followed up by the Posse Comitatus who put the hit out on the Federal Government (6). These organizations go beyond the mainstream into a fanatical fringe that all have a few things in common. First, they do not have a just or moral cause (though they think they do). Their defiance and acts of violence largely stem from disagreement with the mainstream on specific laws, such as gun restrictions, income taxes, the Federal Reserve, the 14th Amendment, and public lands regulation. Second, they believe that the federal government acts in opposition to the Constitution and believe that they not only are protecting and upholding the values set forth in the Constitution, but that they are the ones who truly understand it. Third, they have a very narrow view of which parts of the Constitution they deem worthy of protection and interpretation, and they largely ignore all case law and precedent set between the time of the writing of the Constitution and the present day. And Forth, they act outside of the law.

It is a dangerous mixture of narcissism, hatred, and ignorance. The most alarming aspect is that while they cloak themselves in the flag and Constitution, they shred the very principles behind them at the same time. We could rightfully dismiss Cliven Bundy as an ego-maniac with a hero complex, but the problem goes further than his cause célèbre when he takes on followers willing to do his bidding through acts and threats of violence. While it is true that the government can act outside of Constitutional principles or can be corrupt, the mainstream fights it within the confines of the law. Sometimes they win and sometimes they lose, but while they are fighting bad law, the way they go about it shows respect for the rule of law in the process. It is the right and patriotic way to keep out-of-control government in check. There is much to complain about in regard to the legal system and how it works, but allowing radical militias, who interpret the Constitution through an arbitrary and selfish lens, is worse.

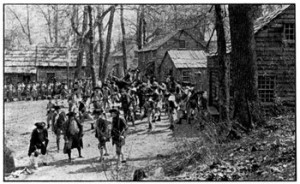

Photo courtesy of http://www.socialstudiesforkids.com

The first such case of a militia taking up arms against the United States Government was a group of whiskey distillers in Pennsylvania in 1791 in response to a tax on whiskey. Treasury Secretary Hamilton needed to find a steady source of revenue for the fledgling government and so he proposed an excise tax on whiskey produced in the United States. Congress instituted the levy in 1791 (1). The whiskey distillers, like modern day Cliven Bundy and his supporters, didn’t like the tax. In response, the hostile farmers “attacked and destroyed the home of a tax inspector (1).” The hostility grew and threatened to spread to other states. At the time, the government was weak and could not withstand this kind of insubordination if it was to succeed. George Washington was President at the time and Hamilton advised him to send in the military. George Washington did not take his advice and first sent in negotiators, but they failed to resolve the issue with the farmers. When diplomacy failed, President Washington sent in a force of 13,000 militia troops, led by Hamilton and Virginia governor Henry Lee, to put the rebellion down in western Pennsylvania. According to Richard H. Kohn, in his article The Washington Administration’s Decision to Crush the Whiskey Rebellion,

“One of the fundamental questions raised in the debates over the Constitution in 1787 and 1788 was on what foundation the ultimate authority of government rested. When they discussed the problem men who differed over the Constitution as much as James Madison and Richard Henry Lee agreed that government was based either on law or on force and that law was the only firm basis on which to build a healthy republican society. And they also agreed that once the law failed, either through individual disobedience or riot and rebellion, force would be necessary to restore order and compel citizens to fulfill their social obligations (2).”

While the U.S. government is no longer a fledgling one, the similarities between the whiskey farmers in the 1790s and modern day Cliven Bundy and his supporters are striking. The only real difference is the amount of force used by the government to quell the Bunkerville insurrection. But the question about the breakdown of law and the use of force is still relevant. The prospect of force being the final arbiter of justice is truly frightening because it indicates that the rule of law has been breached. This breach of law is the chipping away at the foundation on which this country rests; contrary to the popular and romantic view that it is based on peoples’ willingness to rise up against the government. Furthermore, it puts everyone at risk, including the rebels themselves. The very laws that they are undermining are also protecting them against a real Wild West showdown, not just between them and the government, but by other citizens willing to play by their rules. What is truly shocking, however, is how prevalent this rural defiance is and how it has been allowed, some might even say encouraged, to go unchallenged for so long in the state of Nevada.

There is a certain romanticism attached to the West, and it holds throughout the country, not just in the West. There is some reason for it. When the West was being settled, it really was wild. Justice was largely held in the streets and tough, hardscrabble people had to find a way to survive in what was an unruly part of the country lacking law and order. Against all the odds, tenacious individuals managed to tame the land, endure the lack of law and order, and settle here. Those who came here had to rely on themselves in part because the government was not established enough to do it. But with that self-reliance and individualism came an almost inherited attitude of entitlement to be free from all restraints, regulations, or rules, including from the government. Of course when the government did grow in strength and capability, the rough and tumble settlers of the West viewed it as the new and ever encroaching monster they must now face, and it fit well in their Wild West worldview. In fact, when the Bundy showdown began, the phrase, “It’s about to get western down there,” was touted repeatedly by Bundy supporters. It appeared that these people were excited at the prospect of going toe-to-toe with the government and felt they were following in a glorious tradition started by none other than, the Founding Fathers.

On Independence Day in 2000 a group of roughly 300 people in the small town of Jarbridge Nevada took up shovels and headed to a narrow road on federal land that had been closed by the Forest Service in 1995 after a flood had washed it out. The Forest Service determined that the construction to repair the road would cause more harm than good by endangering the river’s dwindling population of bull trout via erosion. “Long angered by federal restrictions on everything from water access to grazing rights, county officials and anti-federalists across the West seized upon the obscure road as a symbol of their discontent. “We will rebuild the road, come hell or high water,” declared Tony Lesperance, an Elko County commissioner. The demonstrators, met by dozens of law enforcement officers and media cameras, paraded down Main Street, brandishing their shovels and singing The Star Spangled Banner (3).” Due to the media being there, and people excitedly giving interviews, it got a lot of coverage.

“It was a classic fin-de-siècle American protest: a staged telegenic moment steeped in Western symbolism,” according to Mother Jones reporter Florence Williams.

But that’s not the worst of it. According to Williams, Elko County Nevada has earned the reputation as the most lawless county in the West. “In 1995, on the same day a bomb exploded in a Forest Service building across the state in Carson City, a detonated pipe bomb was discovered in an outhouse at a campground near Elko, the county seat (3).” On August 5, 1995 according to the AP, “A bomb exploded under a van at the home of a U.S. Forest Service ranger whose office was shattered by a pipe bomb four months earlier. The bomb was either thrown or placed underneath the van of District Ranger Guy Pence, parked in the driveway of his house. The explosion destroyed the van and broke a few windows in Pence’s home. Pence was on a horseback trip in central Nevada but his wife and three children were in the house in a quiet residential neighborhood on the south side of Nevada’s capital city.”

Photo courtesy http://www.blm.gov

Luckily, none of them were hurt. This happened around the time that the Unabomber killed the head of the California Forestry Association and the Oklahoma City bombings occurred (Timothy McVeigh was associated with the Sovereign Citizen Movement, an anti-federal movement, that showed up to support Cliven Bundy, among others). The bombing at Pence’s office and home were the first on a federal facility or employee in Nevada since Halloween 1993, when a bomb was tossed onto the roof of the federal Bureau of Land Management’s state headquarters in Reno. It is shocking to consider that rural ranchers were so upset over land issues that they would risk killing innocent federal employees trying to do their jobs.

“Federal employees and their families have been harassed and threatened by local residents, prompting some to resign. Snowmobilers venture into protected habitats, ranchers ‘trespass’ their cows on pastures set aside as off-limits, and residents take firewood from federal lands and forests without permits. In Jarbidge, even local politicians have abandoned civility and due process. Two county commissioners feuding over floor time at a public meeting had to be physically separated by the sheriff, and the former publisher of the local paper expressed his civic spirit by shooting an officer’s dog in the middle of town (3).” I recently spoke with a former Forest Service employee who worked in Nevada who said,

“It was very isolated and we were warned from the beginning that most of the people in town were not fond of the Forest Service or BLM. We were the “outsiders”. We were advised to live in the “compound” (government housing). We didn’t eat at the local café because we were told that they would mess with our food. Some people were nice to us but not many. So, we USFS employees just stuck to ourselves mostly. The residents had more disdain for federal law enforcement officers, though. And, there were certain families or individuals that were more notorious about it than others. I would say that most people were just indifferent to us, though. In fact, we never locked our front door. It was a very odd situation. On the one hand, we knew the political history of the area and who the more vocal main players were. We were always careful and safe, but I never felt like I was in any real danger while we lived there. It was just understood that certain residents got away with certain things because they knew that there was little that we could do about it. We were just too short staffed and had too large of an area to cover. It was more an atmosphere of veiled threats and intimidation.

That being said, there were certain people who stirred the pot quite a bit. Wayne Hage and his wife, former US Congresswoman Helen Chenoweth, were the ones who informed my husband of his illegitimacy as an armed federal law enforcement officer and that he was a trespasser. I remember sitting in their beautiful ranch home and listening to them smugly recite their ideology and attempt to justify it by quoting parts of the US Constitution.

Another infamous character was Dick Carver of Nye County. He was a former county commissioner and Sagebrush rebel who was known to carry a copy of the US Constitution in his shirt pocket. He took it upon himself to use his bulldozer to open up a closed FS road. Also, the Nye county sheriff’s office was well known to support Carver and his ideology. They were openly uncooperative with any federal law enforcement efforts.”

But worse than that, they were and are undermining their very own State Constitution. Their paradoxical and contradictory stance is astounding to the reasonable mind, especially when assertions of illegal federal law enforcement within the state is brought up. Article 1, Section 2 of the Nevada Constitution:

All political power is inherent in the people. Government is instituted for the protection, security and benefit of the people; and they have the right to alter or reform the same whenever the public good may require it. But the Paramount Allegiance of every citizen is due to the Federal Government in the exercise of all its Constitutional powers as the same have been or may be defined by the Supreme Court of the United States; and no power exists in the people of this or any other State of the Federal Union to dissolve their connection therewith or perform any act tending to impair, subvert, or resist the Supreme Authority of the government of the United States. The Constitution of the United States confers full power on the Federal Government to maintain and Perpetuate its existence, and whensoever any portion of the States, or people thereof attempt to secede from the Federal Union, or forcibly resist the Execution of its laws, the Federal Government may, by warrant of the Constitution, employ armed force in compelling obedience to its Authority (7).

Why is this happening? Furthermore, why are politicians promoting this type of behavior instead up upholding the laws of the land and the state? Part of the answer is that there is an ideological shift taking place in the West, at a national level, from the extractive industries to an increased emphasis on protecting the environment. As these national priorities have shifted, the rural way of life has slowly declined and has left many feeling insignificant and neglected. Because most of the growth in Nevada has happened in Las Vegas and Reno, many rural people feel left out of the loop. Perhaps they feel that violence and rebellion is their only option to get heard, but in the continued conflict over how to deal with the change and growing divide over land use, violence and outright defiance to the law is doing more to hurt their cause – even if they have a worthy one. Furthermore, any reasonable person with a sympathetic or willing ear will disappear when this road is taken.

“In Nevada, resentment over the land dates back to the state’s founding. Settlers had expected to take possession of much of the land after the territory was admitted to the Union in 1864. But to the dismay of miners, ranchers, and loggers, most of the state remained in the public domain, and millions of acres were eventually preserved as national forests or placed under the direction of the federal Bureau of Land Management. The deep-seated seething came to a head in 1977. Angered by federal moves to increase fees for ranchers who grazed livestock on public lands and to set aside millions of acres as wilderness areas, the Nevada legislature backed a legal challenge to claim most of the federal land. Other Western states quickly followed suit, launching a regional movement that became known as the Sagebrush Rebellion (3).”

Photo courtesy of http://www.quickmoneyanswers.com

The Sagebrush Rebellion did have rural support and was fought by politicians, but ultimately a federal judge ruled against them. Much of the bravado and angst is egged on by politicians who may gain political capital, but who do not feel the national pinch that comes in response to such rebellions. “Federal ownership of western lands powerfully shapes the regional economy and society. Along with aridity, it is perhaps the defining characteristic of the West. Though a national park can be a source of pride; most federal land ownership (especially BLM jurisdiction) has always been a politically attractive whipping boy for western politicians (5).”

One such politician was Richard H. Bryan, who used the cause as a stepping stone to higher office. He argued before the court that Nevada, along with other states, had an expectancy upon admission into the Union that the unappropriated, unreserved and vacant lands within their borders would be disposed of by patents to private individuals or by grants to the States and that federal control of lands within western states’ borders prevented those states from standing on an equal footing with other states, as required by the Constitution. U.S. District Court Judge Reed cited the Property Clause within the Constitution and ruled against him. But like Nevada before, states such as Utah and Montana are still willing to gamble with the opportunity to successfully fail and further chip away at the harmony that law and knowledge of the law provide (5).

In the battle in Jarbridge over the Forest Service road, Republican state assemblyman John Carpenter and other elected officials were leading the charge (among many before it). Elko County claimed that it, not the federal government, owned South Canyon Road under an obscure federal statute dating from 1866, known as R.S. 2477. The statute essentially guaranteed settlers rights-of-way across federal land. When the Forest Service failed to repair the road after the flood, the County Commission decided to do it on its own, without bothering to obtain the appropriate permits. After the county had already filled in 900 feet of wetlands and changed the course of the Jarbidge River, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Nevada Department of Environmental Protection got an injunction against the county for violating the Clean Water Act. In 1999, Carpenter and two of his allies — attorney Grant Gerber and county GOP chairman O.Q. Chris Johnson — organized a group to reopen the road. Threatened with a federal restraining order, the men turned back, but they continued to spur on the Shovel Brigade (3).

A federal district judge ordered Elko County and the Forest Service into mediation to resolve their dispute over the road. After 100 days, the two sides reached a proposed settlement that gave the county essentially everything it wanted: a nice new road farther away from the fish, paid for by the feds. The agency even agreed to give the county the authority to maintain the road in the future. But the agreement stopped short of explicitly stating that the county “owned” the road. That wasn’t enough to satisfy Carpenter and many county officials, even though the county’s own negotiators had hammered out the terms. The County Commission refused to sign the settlement (3). This refusal to compromise is a consistent trend amongst such radicals, as we saw when Cliven Bundy refused to cooperate and demanded all law enforcement officers hand over the guns, the government disband the BLM and NPS, and that gates be torn down at National Parks.

Such actions and bravado are exasperating to citizens and county officials who are fed up with the anti-federalists. According to Williams, Karen Dredge, who retired after 17 years as Elko County clerk, pointed out how nobody stepped forward to help underwrite the county’s failed lawsuit over rancher Don Duval’s water rights. “The county is broke,” says Dredge. “We were told to cut all our departments’ budgets, and they want to fight a cause that really strays from county business. Some of our commissioners are activists, not leaders. It’s a room full of the same radical people with the same radical words, and they want us to foot the bill.” In Elko County, the anti-federal attitude comes from the top. In the late 1990s the district attorney drafted a public service announcement advocating discrimination against Forest Service employees. “This message is brought to you by the Elko County Commission, who encourages you to let the Forest Service know what you think about this by not cooperating with them,” the draft read. “Don’t sell goods or services to them until they come to their senses.” The commission did not act on the district attorney’s advice, but hostilities became so great that Gloria Flora, supervisor of the Humboldt-Toiyabe, resigned from her job in 1999, saying she feared for the safety of her employees (4).

This sort of rhetoric can be heard around St. George and on the Stand with the Bundy’s Facebook page encouraging people to refuse service to federal employees. Several federal employees at the St. George Field Office, who had nothing to do with Bundy’s roundup, got enough threats that they were sent home. It is people in positions of authority, whether they are church leaders, media types, or politicians, who are culpable if not flat out guilty, in promoting this destructive attitude and lawlessness. But they are not the ones who will pay. They may get a pat on the back from their fellow church goers, or their buddies, or gain some political clout, but once it’s over, they will go back to their regular jobs, homes, and life while the rural community suffers the backlash. Some of those local politicians include Utah Senator Mike Lee (who ran against Senator Bennett on none other than the issue of public lands) and Governor Herbert (suing the Federal Government for public lands and access roads), the Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott, and Governor Sandoval in Nevada.

But political maneuvering aside, this really hurts rural communities and people. The trend across the West is changing, whether people like it or not. It is going to take smart people to find fair and equitable solutions, not ignorant people bent on working out their differences through violence. People in rural communities need to be included in the march of progress and helped economically rather than left behind once they have helped greedy politicians move up the political ladder. According to Williams, “Many residents fear that the alpha-male approach to conflict resolution prevents the local economy from diversifying beyond casinos and gold mining. This is certainly not good for economic development, worries Glen Guttry, an Elko city councilman. Some people are afraid to move in because of all the controversy (3).”

Seething anger, conflict, and a stubborn hold on the past will kill any attempt at a flourishing economy for rural communities by scaring away investors, businesses, and people who might otherwise be interested. I once spoke with a rancher who was bemoaning snotty east coast college graduates that come out to the West and tell him how the range works. I suggested that he offer internships so that they could learn what he was talking about. He mused on that. I would posit that rural people need to take time off to get degrees in biology, geology, law enforcement, environmental science, and law, etc., and then go back to their communities better equipped to help them. Perhaps even get jobs within land management agencies where their unique perspective can shed light on situations that would otherwise not get it.

As old Marshal Cogburn said in True Grit, “If you don’t have no schooling you are up against it in this country, sis. That is the way of it. No sir, that man has no chance any more. No matter if he has got sand in his craw, others will push him aside, little thin fellows that have won spelling bees back home.” Might and grit will only get you so far, and will do more for opportunistic politicians than the regular citizen. It appears that Nevada is as lawless as ever. It is time for those with sway and power to be the voice of reason and help the people of rural Nevada transition to the New West with respect and dignity and encourage rural Nevadans to give dignity, respect, and fair treatment to the federal employees caught in the middle. Smarter not harder comes to mind. Cliven Bundy is in the limelight right now, but it won’t last, and the consequences of his actions may turn out to be more toxic to the rural individual than the Federal Government ever could be.

For more history on the Posse Comitatus that started during the reconstruction of the South, the Sovereigns Movement, and Cliven Bundy’s link to them and his stance on sheriffs being the final authority, etc.

Sources:

(1) PBS Whiskey Rebellion: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/duel/peopleevents/pande22.html

(2) Richard H. Kohn, The Washington Administration’s Decision to Crush the Whiskey Rebellion: http://arch.neicon.ru/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/4145794/JournalofAmericanHistoryjah_59_3_59-3-567.pdf?sequence=1

(3) Mother Jones, The Shovel Rebellion: http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2001/01/shovel-rebellion

(5) Story of Kleppe v. New Mexico: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1454&context=facpub

(6) A long history of armed Constitutional vigilantism predates Bundy Ranch: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2014/04/bundy_ranch_vigilantism_going_mainstream_the_idea_that_the_constitution.2.html

(7) The Irony of Cliven Bundy’s Unconstitutional Stand, by Matt Ford: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/04/the-irony-of-cliven-bundys-unconstitutional-stand/360587/