Blog Archives

Who Should Manage Public Lands within Utah

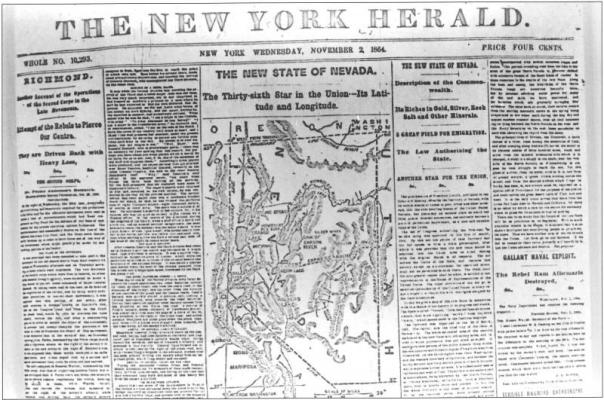

The Salt Lake Tribune’s sponsored debate on public lands management in Salt Lake City May 14th, 2014. This debate is is being had in many other western states as well who are teaming up with Utah in it’s battle against the Federal Government for public lands. It seems to me that Nevada already tried this argument and lost, albeit without the ‘duty to dispose’ theory.

Utah Enabling Act – Section in Question:

“That the people inhabiting said proposed State to agree and declare that they forever disclaim all right and title to the unappropriated public lands lying within the boundaries thereof; and to all lands lying within said limits owned or held by any Indian or Indian tribes; and that until the title thereto shall have been extinguished by the United States, the same shall be and remain subject to the disposition of the United States, and said Indian lands shall remain under the absolute jurisdiction and control of the Congress of the United States; that the lands belonging to citizens of the United States residing without the said State shall never be taxed at a higher rate than the lands belonging to residents thereof; that no taxes shall be imposed by the State on lands or property therein belonging to or which may hereafter be purchased by the United States or reserved for its use; but nothing herein, or in the ordinance herein provided for, shall preclude the said State from taxing, as other lands are taxed, any lands owned or held by any Indian who has severed his tribal relations and has obtained from the United States or from any person a title thereto by patent or any other grant, save and except such lands as have been or may be granted to any Indian or Indians under any Act of Congress containing a provision exempting the lands thus granted from taxation; but said ordinance shall provide that all such land be exempt from taxation by said State so long and to such extent as such Act of Congress may prescribe.”

Ranching rears its head again:

“Until the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, a substantial amount of federal land was still being unloaded each year, but that law ended the homesteading era where the goal had been to transfer federal land to state and private ownership. The Taylor Grazing Act authorized the Interior to put 80 million acres of land into grazing districts, which required users to get permits, pay fees, and follow federal regulations. Federal land sales slowed to a trickle, and the last major disposal of federal lands was in 1980 when Congress turned over several million acres of land to the state of Alaska and Native Americans in that state.

Robert Nelson has noted that “federal ownership of vast areas of western land is an anomaly in the American system of private enterprise and decentralized government authority. As such, there have been occasional revolts against federal land ownership in the West, such as the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s. Two developments that helped spur that rebellion were a 1974 environmental lawsuit that threatened to restrict grazing rights and the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which declared that existing federal lands would remain in federal ownership. Western states led by Nevada fought back with legislation aimed at transferring federal lands to state ownership. However, the revolt fizzled out when ranchers and other users of federal land realized that they might not receive the same level of subsidies they currently received if land ownership was changed. The anti-Washington rally cry of the Sagebrush Rebellion had popular appeal, but the special interests that rely on the inexpensive use of federal lands helped to block reforms.”

– See more at: http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/interior/reforming-federal-land-management#sthash.dPTRCF2K.dpuf

Until the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, a substantial amount of federal land was still being unloaded each year, but that law ended the homesteading era where the goal had been to transfer federal land to state and private ownership.9 The Taylor Grazing Act authorized Interior to put 80 million acres of land into grazing districts, which required users to get permits, pay fees, and follow federal regulations. Federal land sales slowed to a trickle, and the last major disposal of federal lands was in 1980 when Congress turned over several million acres of land to the state of Alaska and Native Americans in that state.

Robert Nelson has noted that “federal ownership of vast areas of western land is an anomaly in the American system of private enterprise and decentralized government authority.”10 As such, there have been occasional revolts against federal land ownership in the West, such as the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s. Two developments that helped spur that rebellion were a 1974 environmental lawsuit that threatened to restrict grazing rights and the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which declared that existing federal lands would remain in federal ownership.11 Western states led by Nevada fought back with legislation aimed at transferring federal lands to state ownership. However, the revolt fizzled out when ranchers and other users of federal land realized that they might not receive the same level of subsidies they currently received if land ownership was changed. The anti-Washington rally cry of the Sagebrush Rebellion had popular appeal, but the special interests that rely on the inexpensive use of federal lands helped to block reforms.

– See more at: http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/interior/reforming-federal-land-management#sthash.dPTRCF2K.dpuf

Until the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, a substantial amount of federal land was still being unloaded each year, but that law ended the homesteading era where the goal had been to transfer federal land to state and private ownership.9 The Taylor Grazing Act authorized Interior to put 80 million acres of land into grazing districts, which required users to get permits, pay fees, and follow federal regulations. Federal land sales slowed to a trickle, and the last major disposal of federal lands was in 1980 when Congress turned over several million acres of land to the state of Alaska and Native Americans in that state.

Robert Nelson has noted that “federal ownership of vast areas of western land is an anomaly in the American system of private enterprise and decentralized government authority.”10 As such, there have been occasional revolts against federal land ownership in the West, such as the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s. Two developments that helped spur that rebellion were a 1974 environmental lawsuit that threatened to restrict grazing rights and the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which declared that existing federal lands would remain in federal ownership.11 Western states led by Nevada fought back with legislation aimed at transferring federal lands to state ownership. However, the revolt fizzled out when ranchers and other users of federal land realized that they might not receive the same level of subsidies they currently received if land ownership was changed. The anti-Washington rally cry of the Sagebrush Rebellion had popular appeal, but the special interests that rely on the inexpensive use of federal lands helped to block reforms.

– See more at: http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/interior/reforming-federal-land-management#sthash.dPTRCF2K.dpuf

Until the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, a substantial amount of federal land was still being unloaded each year, but that law ended the homesteading era where the goal had been to transfer federal land to state and private ownership.9 The Taylor Grazing Act authorized Interior to put 80 million acres of land into grazing districts, which required users to get permits, pay fees, and follow federal regulations. Federal land sales slowed to a trickle, and the last major disposal of federal lands was in 1980 when Congress turned over several million acres of land to the state of Alaska and Native Americans in that state.

Robert Nelson has noted that “federal ownership of vast areas of western land is an anomaly in the American system of private enterprise and decentralized government authority.”10 As such, there have been occasional revolts against federal land ownership in the West, such as the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s. Two developments that helped spur that rebellion were a 1974 environmental lawsuit that threatened to restrict grazing rights and the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which declared that existing federal lands would remain in federal ownership.11 Western states led by Nevada fought back with legislation aimed at transferring federal lands to state ownership. However, the revolt fizzled out when ranchers and other users of federal land realized that they might not receive the same level of subsidies they currently received if land ownership was changed. The anti-Washington rally cry of the Sagebrush Rebellion had popular appeal, but the special interests that rely on the inexpensive use of federal lands helped to block reforms.

– See more at: http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/interior/reforming-federal-land-management#sthash.dPTRCF2K.dpuf

A legal defense of Utah’s H.B. 148: http://dnr.alaska.gov/commis/cacfa/documents/FOSDocuments/UtahLegalOverviewofUT_HB148.pdf